Stellar pulsations

Stellar pulsations are caused by expansions and contractions in the outer layers as a star seeks to maintain equilibrium. These fluctuations in stellar radius causes corresponding changes in the luminosity of the star. Astronomers are able to deduce this mechanism by measuring the spectrum and observing the Doppler effect.[1] Many intrinsic variable stars that pulsate with large amplitudes, such as the classical Cepheids, RR Lyrae stars and large-amplitude Delta Scuti stars show regular light curves. (By regular one means that Fourier analysis shows amplitudes that are constant in time.)

This regular behavior is in contrast with the variability of stars that lie parallel to and to the high-luminosity/low-temperature side of the classical variable stars in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. These giant stars are observed to undergo pulsations ranging from weak irregularity, when one can still define an average cycling time or period, (as in most RV Tauri stars and Semiregular variables) to the near absence of repetitiveness in the Irregular variables. The W Virginis variables are at the interface; the short period ones are regular and the longer period ones show first relatively regular alternations in the pulsations cycles, followed by the onset of mild irregularity as in the RV Tauri stars into which they gradually morph as their periods get longer.[2][3] Stellar evolution and pulsation theories suggest that these irregular stars have a much higher luminosity to mass (L/M) ratios.

A third category of variable stars are the non-radial pulsators which typically have much smaller pulsation amplitudes. With relative fluctuations in brightness from ~10\% down the observable limit, non-radial pulsation is very common among stars.[4][5]

Here we address the mathematical and physical reasons for the difference between the regular and irregular large amplitude stars. Intuitively, a prerequisite for irregular variability is that the star be able to change its amplitude on the time scale of a period. In other words, the coupling between pulsation and heat flow must be sufficiently large to allow such changes. This coupling is measured by the relative linear growth- or decay rate  of the amplitude of a given normal mode in one pulsation cycle (period). For the regular variables (Cepheids, RR Lyrae, etc) numerical stellar modeling and linear stability analysis show that

of the amplitude of a given normal mode in one pulsation cycle (period). For the regular variables (Cepheids, RR Lyrae, etc) numerical stellar modeling and linear stability analysis show that  is at most of the order of a couple of percent for the relevant, excited pulsation modes. On the other hand, the same type of analysis shows that for the high L/M models

is at most of the order of a couple of percent for the relevant, excited pulsation modes. On the other hand, the same type of analysis shows that for the high L/M models  is considerably larger (30% or higher).

is considerably larger (30% or higher).

Regular Variables

For the regular variables the small relative growth rates  imply that there are two distinct time scales, namely the period of oscillation and the longer time associated with the amplitude variation. Mathematically speaking, the dynamics has a center manifold, or more precisely a near center manifold. In addition, it has been found that the stellar pulsations are only weakly nonlinear in the sense that one can limit oneself to low powers of the pulsation amplitudes to describe them. These two properties are very general and occur for oscillatory systems in many other fields such as population dynamics, oceanography, plasma physics, etc.

imply that there are two distinct time scales, namely the period of oscillation and the longer time associated with the amplitude variation. Mathematically speaking, the dynamics has a center manifold, or more precisely a near center manifold. In addition, it has been found that the stellar pulsations are only weakly nonlinear in the sense that one can limit oneself to low powers of the pulsation amplitudes to describe them. These two properties are very general and occur for oscillatory systems in many other fields such as population dynamics, oceanography, plasma physics, etc.

The weak nonlinearity and the long time scale of the amplitude variation can be taken advantage of to reduce the temporal description of the pulsating system to that of only the pulsation amplitudes, thus eliminating motion on the short time scale of the period. The result is a description of the system in terms of amplitude equations that are truncated to low powers of the amplitudes. Such amplitude equations have been derived by a variety of techniques, e.g. the Poincaré-Lindstedt method of elimination of secular terms, or the multi-time asymptotic perturbation method[6][7][8], and more generally, normal form theory.[9][10][11]

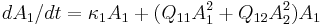

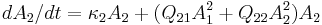

For example, in the case of two non-resonant modes, a situation generally encountered in RR Lyrae variables, the temporal evolution of the amplitudes A1 and A2 of the two normal modes 1 and 2 is governed by the following set of ordinary differential equations

where the Qij are the nonresonant coupling coefficients.[12][13]

These amplitude equations have been limited to the lowest order nontrivial nonlinearities. The solutions that interest us in stellar pulsation theory are the asymtotic solutions (time → infinity) because the time scale for the amplitude variations is generally very short compared to the evolution time scale of the star which is the nuclear burning time scale. The equations above have fixed point solutions with constant amplitudes, corresponding to single-mode (A1 0, A2 = 0) or (A1 = 0, A2

0, A2 = 0) or (A1 = 0, A2 0) and double-mode (A1

0) and double-mode (A1 0, A2

0, A2 0) solutions. These correspond to singly periodic and doubly periodic pulsations of the star. It is important to emphasize that no other asymptotic solution of the above equations exists for physical (i.e., negative) coupling coefficients.

0) solutions. These correspond to singly periodic and doubly periodic pulsations of the star. It is important to emphasize that no other asymptotic solution of the above equations exists for physical (i.e., negative) coupling coefficients.

For resonant modes the appropriate amplitude equations have additional terms that describe the resonant coupling among the modes. The Hertzsprung progression in the light curve morphology of classical (singly periodic) Cepheids is the result of a well-known 2:1 resonance among the fundamental pulsation mode and the second overtone mode[14]. The amplitude equation formalism can be further extended also to nonradial stellar pulsations.[15][16]

In the global analysis of pulsating stars, the amplitude equations make possible to map out the bifurcation diagram (see also bifurcation theory) between the possible pulsational states, such as the various single- and double-mode states[17]. In this picture, the boundaries of the instability strip where pulsation sets in during the star's evolution correspond to a Hopf bifurcation.

The existence of a center manifold eliminates the possibility of chaotic (irregular) pulsations on the time scale of the period. Although resonant amplitude equations are sufficiently complex to also allow for chaotic solutions, this is a very different chaos because it is in the temporal variation of the amplitudes and occurs on a long time scale.

One sees that while long term irregular behavior in the temporal variations of the pulsation amplitudes is possible when amplitude equations apply, this is not the general situation. Indeed, for the majority of the observations and modeling, the pulsations of these stars occur with constant Fourier amplitudes, leading to regular pulsations that can be periodic or multi-periodic (quasi-periodic in the mathematical literature).

Irregular Pulsations

For high L/M stars no center manifold exists because of their large relative growth rates  , and consequently there exist no amplitude equations to help us understand these pulsations. The large

, and consequently there exist no amplitude equations to help us understand these pulsations. The large  are a prerequisite for chaos, although not a sufficient condition (see for example the Shilnikov theorem [1]). Completely different techniques are required for understanding chaotic behavior (see Chaos theory). There are both observational and numerical hydrodynamical results strongly suggesting that, at least in some well-studied cases, the variability is due to a low dimensional chaotic dynamics. The observational evidence is particularly strong for the star R Scuti (see Low dimensional chaos in stellar pulsations).

are a prerequisite for chaos, although not a sufficient condition (see for example the Shilnikov theorem [1]). Completely different techniques are required for understanding chaotic behavior (see Chaos theory). There are both observational and numerical hydrodynamical results strongly suggesting that, at least in some well-studied cases, the variability is due to a low dimensional chaotic dynamics. The observational evidence is particularly strong for the star R Scuti (see Low dimensional chaos in stellar pulsations).

References

- ^ Koupelis, Theo (2010). In Quest of the Universe. Jones and Bartlett Titles in Physical Science (6th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 0763768588. http://books.google.com/books?id=GVlpKZ67DscC&pg=PA401.

- ^ Alcock, C. et al. 1998, The MACHO Project LMC Variable Star Inventory. VII. The Discovery of RV Tauri Stars and New Type II Cepheids in the Large Magellanic Cloud, Astronomical Journal, 115, 1921

- ^ Soszyński, I. et al. 2008, The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment. The OGLE-III Catalog of Variable Stars. II.Type II Cepheids and Anomalous Cepheids in the Large Magellanic Cloud, Acta Astronomica, 58, 293

- ^ Grigahcéne, A., et al. 2010, Hybrid γ Doradus- δ Scuti Pulsators: New Insights into the Physics of the Oscillations from Kepler Observations, Astrophysical Journal, 713, 192

- ^ Mosser, B., et al. 2010, Red-giant seismic properties analyzed with CoRoT, to appear in Astronomy and Astrophysics (arXiv1004.0449)

- ^ Dziembowski, W. 1980, Delta Scuti variables - The link between giant- and dwarf-type pulsators, Lecture Notes in Physics, 125, 22

- ^ Buchler, J. R. and Goupil, M. J. 1984, Amplitude Equations for Nonadiabatic, Nonlinear Stellar Pulsators, I. The Formalism, Astrophysical Journal 279, 394

- ^ Buchler, J.R. 1993, A Dynamical Systems Approach to Nonlinear Stellar Pulsations, Astrophysics and Space Science, 210, 9

- ^ Guckenheimer, J. and Holmes, P. 1982, Nonlinear oscillations, dynamical systems, and bifurcations of vector fields, in Applied Mathematical Science, New York: Springer

- ^ Coullet, P. and Spiegel, E. A. 1984, SIAM J. Appl. Math., 43, 776

- ^ Spiegel, E. A. 1985, Cosmic Arrhythmias in Chaos in Astrophysics, Eds. J. R. Buchler, J. M. Perdang, and E. A. Spiegel, NATO ASI Series, C161, 91, Reidel Publisher

- ^ Buchler, J. R. and Kovacs, G. 1987, Modal selection in stellar pulsators. II - Application to RR Lyrae models, Astrophysical Journal, 318, 232

- ^ Van Hoolst, T. 1996, Effects of nonlinearities on a single oscillation mode of a star, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 308, 66

- ^ Buchler, J. R., Moskalik, P. Kovacs, G. 1990, A survey of Bump Cepheid model pulsations, Astrophysical Journal, 351, 617

- ^ Van Hoolst, T. 1994, Coupled-mode equations and amplitude equations for nonadiabatic, nonradial oscillations of stars, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 292, 471

- ^ Buchler, J. R., Goupil, M. J. and Hansen C. J. 1997, On the Role of Resonances in Nonradial Pulsators, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 321, 159

- ^ Kollath, Z., Buchler, J. R., Szabo, R. & Csubry, Z. 2002, Nonlinear Beat Cepheid and RR Lyrae Models, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 385, 932

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||